|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Book Thirteen

|

|

|

|

Now Zeus (zyoos) turns his attention elsewhere, and Poseidon (puh-SY-dun) sees an opportunity to help the Greeks. Descending from the island mountaintop from which he has been watching the fray, he crosses the entire Aegean Sea in four huge strides, swiftly reaching his submarine palace. Here he harnesses his team of bronze-hooved, golden-maned stallions and returns to Troy, his chariot skimming over the waves as dolphins sport in his wake. Unwilling to risk Zeus's wrath by intervening directly, Poseidon adopts a mortal form in which to harangue the Greeks to action. He spurs Great and Little Ajax with his words and invests their bodies with new vigor. The men are not so foolish as to fail to recognize a god, and they comment with exhilarated detachment on the way their own feet are rushing them toward combat.

|

|

|

|

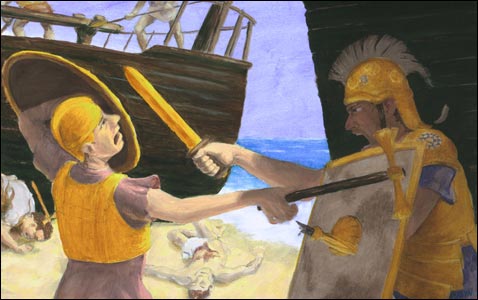

In the desperate fighting at close quarters amidst the ships of the Greek encampment, the means of meeting death are varied and ghastly. Poseidon's own grandson Amphimachus (am-FIM-uh-kus) is killed by Hector, and in revenge Little Ajax decapitates an adversary and sends his head rolling to Hector's feet. Idomeneus (eye-DOM-en-yoos), grandson of king Minos (MY-noss) of Crete (kreet), spears a Trojan in the chest, and as he crashes down on his back the last beats of his heart jerk the spear from side to side. Idomeneus' second-in-command Meriones (meh-RY-uh-neez) inflicts a wound considered to be the worst of all, stabbing his adversary just below the navel and causing him to writhe in anguish until the spear is yanked out again and he dies.

|

|

|

|

And Menelaus (meh-neh-LAY-us) gains some measure of satisfaction for the Trojans' abuse of his hospitality and abduction of his wife by bashing an adversary right between the eyes with his sword, so that the bone shatters and the man's eyeballs fall to the dirt before he topples. We glimpse the particular sights of battle in this bygone age, when the glare of sunlight on bronze helmets, breastplates, and shields is blinding. We learn more of tactics and weaponry, as the followers of Little Ajax are said to have no love of hand-to-hand combat, preferring to stay at a safe distance in the rear and darken the sky with arrows and lethal shot from their woolen slings. And we overhear an observation about warfare in all epochs, when Idomeneus says to Meriones that you can always tell the cowards by the very way their skin turns white and their teeth chatter as they dread a gruesome fate.

|

|

|

|

Hector comes upon his brother Paris in the melee and upbraids him as usual for being more lady's man than warrior. But this time Paris is innocent of the charge, as he has been in the thick of the fighting all day. He recounts the toll of fallen comrades and then pledges to follow his brother once more into the fray.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|